The first mention of whistling tongues is found in Herodotus's History, dated to the 5th century BC. e. “Their speech is unlike any other in the world: it resembles the squeak of bats” - this is how he described the cave dwellers of Ethiopia. There is no reliable data on which tribes communicated in this way, but whistling languages can still be heard in the Omo Valley in Ethiopia.

In ancient Chinese texts dating back to the 8th century AD. uh, there is a description of Taoist practice, the name of which can be translated as “Principles of Whistling.” This is one of the earliest works on phonetics: it describes what exercises need to be done to learn how to whistle correctly, and also gives twelve specific whistling techniques, with instructions regarding the position of the tongue and lips, breath control, etc. Whistling poetry was believed to be puts a person into a meditative state. In southern China, whistling communities of the Hmong and Akha people still exist.

The first indisputable historical evidence of the existence of a whistling form of language is found in the work of two Franciscan priests who accompanied the French explorer Jean de Bettencourt, who set out to conquer the Canary Islands in 1402.

In their diary, published under the title "The Canary", the priests Bonthier and Le Verrier mention that the inhabitants of the islands spoke "with two lips, as if they had no tongue."

Thanks to later research, it became known that they were faced with a whistling form of the Berber language.

In the Americas, the earliest evidence of the practice of whistling dates back to 1755, when a Jesuit historian reported a whistling form of speech among the Aygua people of Paraguay: “They use a language which is difficult to learn, because they whistle rather than speak.”

This property—the difficulty of learning whistling languages by those unaccustomed to people outside communities—was later exploited in military operations. During World War II, the Australian Army hired Wam speakers from Papua New Guinea to whistle radio messages that the eavesdropping Japanese could not decipher. The Americans used similar tactics during the First World War - they used the Navajo code letter for communication.

As you can see, whistling languages have existed for a long period of history and have appeared all over the world. Could this unusual form of communication, in which language and musicality intertwine, help us learn more about the origins of language? Charles Darwin proposed the existence of a kind of “musical proto-language.” According to this view, people began to sing before they could speak, perhaps as a kind of courtship ritual.

Like birds, people could demonstrate their virtuosity, strengthen social bonds, and scare away rivals, even if whistling carried no practical information.

However, over time, this practice would make us more precise in controlling our vocal cords, which would lay the foundation for more meaningful utterances.

One of the most respected researchers in the field of whistling languages, Julien Meyer, suggests that whistling was one of the stages in the development of language that pushed people towards more complex communication. He notes that although non-human primates cannot learn to speak, some have learned to whistle.

Bonnie, an orangutan at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., has learned to imitate the simple melodies of her keeper Erin Stromberg, and wild orangutans have adapted to emit a high-pitched whistle by sucking air through a leaf.

Such manifestations indicate that whistling requires less effort than speech, making it an ideal stepping stone on the path to language. If this is true, then whistling signals may have begun as a musical proto-language, and as they became more complex and filled with meaning, they turned into a way of coordinating hunting.

Meyer's research suggests that whistling had a distinct survival advantage for our ancestors: they were able to communicate over a distance without attracting the attention of predators and prey. Later, people learned to control their vocal cords, but whistling tongues continued to be a small but important element of humanity's linguistic repertoire.

Recognition and learning

It is necessary to understand that whistling languages are not separate units, but rather other forms of habitual languages. Only the form of communication changes—the vocal register of speech—while the semantic content remains the same. Thus, whistling speech is a phonetic adaptation of natural language that has appeared for communication over long distances, when it is not possible to see each other face to face or the natural features of the landscape do not allow this.

The principle of whistling speech is simple: while whistling, people simplify and transform familiar words into whistling melodies, syllable by syllable.

Whistlers even emphasize that they whistle exactly as they think in their language, and that the whistling messages they receive are instantly interpreted as ordinary speech. In most cases, experienced native speakers can whistle through any information and recognize non-standardly constructed sentences.

Another important feature that makes whistling stand out from a whisper or shout is its inaudibility for people from the outside. It cannot be called completely unique - after all, it can be difficult to understand opera singing even in your native language. But in the case of whistling, people often perceive it not as communication, but rather as a joke. Perhaps it is this aspect of secrecy that has allowed whistling languages to survive for so long. At the same time, this mystery has significantly limited possible research: whistling languages were discovered by chance, and the number of speakers is decreasing every year.

They learn whistling in the same way as any language. Children subconsciously become accustomed to whistling speech signals if they hear them often enough, but mastering them takes a little longer. A child who speaks at 3 or 4 years old understands whistling language at 5–6 years old, but only masters it well by 10–12 years old. Another important point is that the vocabulary of whistlers is as rich and multifaceted as in ordinary speech. Another thing is that whistlers usually use a limited set of words that corresponds to their daily activities.

Whistling languages, although found on many continents, persist only in remote or isolated communities.

They are not limited to a specific territory, language family or structure. Depending on the features of the landscape, patterns of communication are formed: for what needs is whistling used and what equipment is chosen by local residents.

In the forests of Portugal and Brazil, they usually whistle during hunting. As a rule, people are not very far from each other; lips and hands are used to whistle. In the case of the densely forested mountains of Mexico, local people coordinate farming: distances become longer, and lips and teeth are used for communication.

If we talk about steep cliffs with sparse vegetation in Greece, Turkey, Spain or Africa, then shepherding predominates there, the distances are very large, and they resort to using their fingers to whistle. Whistling speech becomes a kind of indicator of the preservation of traditions: the whistling technique requires the transfer of skills from generation to generation, the continuation of the traditional way of life and the presence of the same ecosystem as before. Lifestyles change very slowly due to the isolation of communities: mountains and dense forests slow down the penetration of civilization and limit access to people from outside.

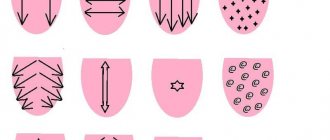

Whistling sounds S - S', Z - Z' and sounds T' - D'

These sounds are anterior lingual at the place of formation.

The tip of the tongue touches the base of the lower incisors.

When the sounds C – Сь, З – Зь are formed, the lateral edges of the tongue fit tightly to the inside of the upper molars, closing the passage of the air stream on the sides.

When producing the sounds Т – Дь in a soft position, the back of the tongue should rise towards the hard palate.

When training these sounds, we encourage students not to stretch their lips in a smile and, if necessary, to avoid a mechanical “grin,” we ask them to hold their cheeks with the thumb and index finger of one hand.

When training whistling sounds, we exaggerately lower our lower lip down.

Sound "Ts"

After the position of the tongue when pronouncing these sounds has been established, you can proceed to the sound “C”. It belongs to the group of affricates (compound sounds). It is formed as a result of the fusion of two sounds: T and S.

Consequently, the tongue performs two successive movements, first touching the roots of the upper teeth, then jumping down and touching the roots of the lower teeth.

Sibilant consonants Ш – Ж – Ш

These sounds are anterior lingual at the place of formation. They hardly differ in the method of articulation.

Sound "Ch"

More complex is the sound “CH”, which consists of sequentially pronounced Ть and Шь. It is advisable to train this sound in the “ clack”

, i.e. “suck” the tongue to the alveoli, and then sharply relax.

When producing hissing sounds, the lateral edges of the tongue are pressed against the upper lateral teeth, not allowing air to pass through the sides.

When articulating these sounds, we strive not to actively move our lips forward and especially pay attention to the upper lip, which, in our deep conviction, should not be very actively raised upward. In some cases, we invite students to hold their upper lip with a pencil placed horizontally on it.

For the correct functioning of the tongue when producing these sounds, we also suggest pressing firmly with your index fingers on the cheeks at the level of the molars. This movement will magically group the tongue into the position we need. It is important to remove your hands and repeat the sound, maintaining the position of your tongue.

The following exercise is effective: bite your tongue on both sides with your molars so that only its front part remains free. Then, holding the sides of the tongue with your teeth, we pronounce the sound repeatedly and relax the tongue. It is important to keep your mouth from “stretching” into a horizontal position.

Dissenting opinion: all sounds should be organized more with the tongue than with the lips.

Sound "R"

When pronouncing the complex sound “R”, you need to make the tip of your tongue vibrate. Sometimes, in difficult cases, we ask the student to lift the tip of his tongue with the smooth and rounded end of the toothbrush and, making quick movements to the left and right, pronounce “D-D-D-D-D-D-D.”

We call this exercise “Machine Gun”.

It is often used in speech therapy practice and practically always helps students.

It is especially difficult to pronounce the sound “R” in combination with the sounds “Zh”

and

"Sh"

. Therefore, we recommend paying closer attention to these combinations and using them more often in diction warm-ups.

Sound "Рь"

Practicing the pronunciation of “Рь” requires special work. You need to start by connecting the sound “R” with the table of iotated vowels: RI – RE – RYA – RE – RYU – RI.

Then we complicate the pronunciation by adding a soft sign: RYE - RYE - RYA - RYE - RYU - RYE.

After this, it makes sense to complicate the exercise as follows: Pb - Pb - PJI, Pb - Pb - PJE, Pb - Pb - PJA, Pb - Pb - PJE, Pb - Pb - PJU, Pb - Pb - PJE.

To train the sounds “P” and “Pb” we use the following exercises: we rotate an imaginary huge steering wheel in front of us with both hands and pronounce the sound “P”. Then, alternately with one or the other, with arms extended forward, we begin to screw in imaginary small screws “Pb – Pb – Pb – Pb...”.

Or an exercise like this. Imagine that we take a thick rubber band at the top with one hand and, pulling it down with force, pronounce “R”. Then, with a quick movement, we stretch this ribbon from left to right, pronouncing “Рь”.

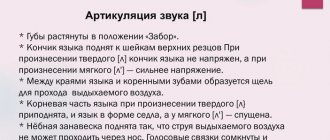

Sound "L"

There are several types of disadvantages in pronunciation of the sound “L”: replacing it with “Y”, “V” and “U”. For example: instead of “word”

They pronounce

“syovo”, “svovo”, “suovo”.

The easiest way to make this sound is the following exercise: bite the tip of your tongue and pull out the “Y” sound. Then you need to pronounce AL – AL – AL, LA – LA – LA, YL – YL – YL, LY – LY – LYS by biting your tongue on the “L” sound. Then you need to move your tongue to the tooth position, press it firmly to the alveoli and repeat the pronunciation of all syllables.

It is also useful to stretch your tongue out of your mouth as much as possible, biting it along its entire length and pronouncing a long “L” sound.

When replacing a sound with “U” and “B”, you need to hold the corners of your mouth with a pencil in the first case, and the lower lip in the second.

While working on this section, we practically do not come up with anything new, believing that the traditional diction exercises existing in the Russian theater school are quite effective. There are wonderful technologies that were developed and described by such famous teachers of the Moscow school as Kozlyaninova, Serova, Saricheva, Charelli, Promtova, Petrova, Zaporozhets and St. Petersburg teachers: Savkova, Kunitsyn, Galendeev, Vasiliev, Latysheva, Filippova, Chernaya, Alferova.

We, like other teachers, give preference to training diction tables, tongue twisters, pure tongue twisters, long tongue twisters and proverbs.

The novelty of our approach lies in the fact that we do not engage in pure reprimand. When performing any diction exercise, we switch students’ attention from the speech-voice apparatus to other objects.

If a student is completely focused on one or another muscle of his speech-voice apparatus, then, it seems to us, he will certainly tighten it. We know that if a person focuses his attention on his throat, it will certainly hurt, and most actors wheeze just before the premiere, for fear of losing their voice. We drew attention to the fact that when training diction tables without adding parallel action, students begin to try very hard and instantly turn into average performers with a leveled individuality. Obviously, in the exercises it is necessary to switch their attention or load them with parallel action, or set creative tasks for them, or organize competitions, etc. In a word, in diction training it is advisable to work on the principle of a game.

Based on these conclusions, we strive for improvisation in every lesson, endlessly modeling new forms of diction play. The actions that accompany the exercises are invented by each student independently and are never repeated twice.

If we flesh out our idea, it becomes obvious that we want to encourage students to fully utilize their creative acting potential in diction and spelling training. Therefore, the exercises that we describe are one of many options for conducting diction training.

During such classes (where speech exercises are accompanied by another action), using difficult-to-pronounce combinations of vowels and consonants arranged in syllable chains, we load the speech muscles to the maximum, developing their activity and mobility.

Syllable chains are built on a combination of consonant sounds with a line of vowels: U - O - A - E - I - Y.

Yotated vowels are built in the following order: Yu – E – Ya – E – I – I.

This line has been adopted and used at the St. Petersburg Theater School. It is characterized by the fact that it is adjusted based on the following position of the larynx: from the lowest position on the sound “U”, to the highest position on the sound “I”, with a slight lowering in the final sound “Y”.

In Moscow schools they use a vowel line in the following order: I – E – A – O – U – Y. It is characterized by the fact that it begins with the closure of the vocal folds on the sound “I”, then the laryngeal muscles follow by lowering the laryngeal muscles to the lowest position on the sound “U”

and return to the top position on “Y”.

We use both vowel chains in training, although we give preference to the Petersburg construction, believing that it is more appropriate and convenient for training.

We distribute consonant sounds in pairs, voiced and unvoiced: “P – B” (labial), V – F (labial-dental), K – G (back-lingual), T – D (front-lingual), Sh – Zh, Ch – Shch (hissing), S - W (whistling). We separately train the sounds C (whistle), X (rear lingual) and L ,

M, N, R (sonorous).

It is fundamentally important that by training the speech apparatus on syllable chains, we simultaneously improve the physical and psychological state of students, offering to connect these syllable chains with active massage of the hands and feet. (see Appendix page).

Exercises

"Modeling"

We imagine that we are holding in our hands an elastically pliable piece of clay. We slowly and actively pronounce the tongue twister, while at the same time fashioning a beautiful flower out of clay. Each petal of our imaginary flower corresponds to one word from the tongue twister.

"Typewriter"

First option.

Let's imagine that we have an old-style typewriter standing in front of us (its keyboard is heavy and in order to type text, you need to work with your fingers with some effort). We begin to type the tongue twister in such a way that the movement of one finger coincides with one word from the tongue twister. The word is pronounced when struck with a finger. For example: Weaves (blow) weaver (blow) fabrics (blow) on (blow) shawls (blow) Tane (blow).

Second option.

We complicate the exercise by starting to “print” each letter of the tongue twister. We make sure that the articulation is as active as the fingers.

This exercise is very useful for developing internal coordination and attention of students.

We have already said that we strive to adjust our classes as much as possible in relation to acting classes. Therefore, in the first semester, when physical action memory (PAM) exercises are taught in mastery classes, we ask students to combine speech syllable chains with these exercises. For example, while pronouncing sounds, a student hammers imaginary nails. Or sews on a button. Or cooks scrambled eggs. Or brushes teeth, etc. When performing this speech exercise, we closely monitor the accuracy of the exercise from the perspective of acting skills. We do not allow any approximation or abstraction in performing a physical action.

In our classes, literally from the first day, we devote special attention to the tempo and rhythm of text pronunciation. We start with simple exercises, well known and widely used in the teaching practice of various theater schools.

Students really enjoy doing the following tasks.

You need to sing a speech syllable chain of sounds to a melody known to everyone. For example, we set up a chain TPI - TPE - TPA - TPO - TPU - TPI - TPI to the tune of the song “Let pedestrians run clumsily through the puddles.”

We sing simple and well-known tunes as a group.

Then we begin to complicate the exercise, inviting the children to sing more complex chains. For example, sing the sound chain PIBIVINIPIFI - PEBEVENEPEFE - PABAVANAPAFA - POBOVONOPOFO - PUBUVUNUPUFU - PYBYVYNYPIFY - PIBIVINIPIFI to the same tune. This is much more difficult to do than the previous version of the exercise.

Then we invite them to come up with their own options. And then come up with them in pairs, threes or small groups. This must be done in homework mode. We present interesting variations of this exercise in an open lesson.

When developing speech tempo-rhythm, we considered it appropriate to combine speech exercises with rhythmic exercises.

Students stand in a checkerboard pattern, one of them comes forward and begins to come up with a separate and simple physical movement for each word of the tongue twister. Thus, the tongue twister is accompanied by a simple rhythmic dance, which students remember and begin to repeat with speed.

During one lesson we do several of these dances, memorize the most interesting ones and also take them to an open lesson.

Sometimes we use well-known dance movements in such exercises, combining the pronunciation of tongue twisters with the subject “dance”. Students, speaking the text, dance a waltz, tango, polka, etc. This kind of combination is useful for the development of both speech and plasticity. But most importantly, they develop coordination of thinking. And this is the primary task of the acting school.

A new problem arises. How to combine acting tasks with clarity of speech. How to make sure that when pronouncing a text clearly, you avoid excessive articulation. Indeed, in natural life a person speaks without active movement of the speech apparatus. Firstly, you need to prove to the student that at the first stage of mastering speech it is necessary to actively engage in articulation. It is necessary to train the entire speech apparatus to such an extent that sounds are formed by micromovements, barely perceptible to the eye. Secondly, we have invented a whole series of exercises aimed at shifting the emphasis away from the lips. The basis of these exercises is to switch attention to other muscle groups. First of all, on the muscles of the tongue.

For example, after articulation gymnastics, we suggest students relax their lower jaw and calm their lip muscles. Then you should pronounce the given text only with your tongue, allowing your lips to close easily only when pronouncing “labial” consonants. At the same time, we ask students to watch the movement of their tongue. This is a difficult exercise to perform, but a fun and effective exercise.

We also use the following technique: after completing any text exercise with active and clear articulation, we make sure to repeat it with relaxed facial muscles.

It is advisable to combine any diction exercise either with a physical action (massage of the hands, feet, ears, head, etc.), or with exercises “for the memory of physical actions” (typewriter, woodcutter, painter, etc.), or with a psychophysical action (argue, call, drive away, etc.).

Thus, already at the stage of technical exercises we strive to make any sound, any exhalation effective. Moreover, even breathing can accurately reflect the slightest movement of the soul. L.D. Alferova describes her feelings from “effective” breathing: “We saw how the actor’s breath reacts, changes and emotionally responds to all the semantic turns in the content of the text. We saw, heard and felt tired, excited, playful, catching, gasping, breathless, dying, convulsive, erotically excited, lazy, sleepy breathing. It was the breath of living people, reacting to events in a real way.”

We are sure that the basis of the actor's profession is the ability to act with words. All major theater and film figures, from K.S. Stanislavsky to P.N. Fomenko, thought about how to make the word effective. That is why in training on seemingly the most elementary texts, we already accustom them to action. And to understanding the action as such. And to its practical application. And to the confidence that action is necessary in any, even the smallest part of the role.

Moving on to exercises based on tongue twisters and tongue twisters, we continue to work on effective pronunciation of the text. Students pronounce tongue twisters and tongue twisters, accurately following the action proposed by the teacher. The teacher suggests using this patter to surprise a partner, or to gossip, or to argue, or to confess love, or to provoke a response, or to intrigue, etc.

At the next stage of work, students choose their own action, without revealing to the rest of the children what action they have chosen. The goal of the course is to guess what a given student is doing.

To correctly perform this exercise, the teacher must clarify that the meaning of the action being performed must be explained in one word. And this word must necessarily be a verb (I order, I ask, I humiliate, I scare, I ask, I clarify, etc.)

APPLICATION

Exercises to improve posture, strengthen and align the spine, and prepare the body for sound production

"Floor ceiling"

Stand straight, feet shoulder-width apart, arms above your head and imagine that the floor and ceiling are actively compressing you. You are a spring that strives to unclench.

"Rope"

Stand straight, heels together, toes apart, hands clasped above your head. Imagine that you are a rope that is being stretched on both sides.

"Hands - tailbone"

Bend so that the body, with arms extended forward, is parallel to the floor. Imagine that you are being actively pulled forward by your arms and backward by your tailbone.

"Cross"

Stand straight, feet together, arms to the sides. Imagine that you are being stretched vertically (by your legs - down, by the top of your head - up), and at the same time - horizontally (by your left hand - to the left, by your right hand - to the right).

Each of these exercises must be done at least four, maximum eight times before each lesson. In addition to the fact that we work on the spine, we also warm up absolutely all muscle groups and after this block we are completely ready for the physical activity that speech-voice training involves.

Examples of whistling languages

As of 2021, there are approximately 70 whistling languages recorded in the world. The most famous and studied habitat of the whistling community is La Gomera, one of the non-tourist Canary Islands. Silbo Gomero was the first whistling language to receive UNESCO living heritage status; it also has the largest number of speakers - about 20 thousand.

The Silbo Gomero language now plays an important role in daily life on the island. It is taught in schools, and is used to attract the attention of tourists - in some restaurants, waiters convey order details by whistling.

Teenagers sometimes earn extra money and put on a whole show for visitors, managing to adapt the whistle for other languages. However, since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, such practices had to be abandoned - putting fingers in the mouth has become unsafe. Now schoolchildren do not practice whistling themselves, but listen to recordings.

The older generation notes that it is more difficult for them to understand young people who learn to whistle at school rather than in the pastures. For them, such a whistle is too elegant and precise, and the vocabulary is richer and more diverse. Elderly residents of La Gomera recall using silbo to alert locals that the police were coming. In the recent Romanian thriller The Whistlers by Corneliu Porumboiu, Silbo is used by gangsters as a secret code language.

On the Greek island of Euboea, in the village of Antia, Sfirian is spoken, the sound of which is reminiscent of bird sounds. Sfiria is one of the most endangered and rare languages in the world. Most native speakers are farmers and shepherds.

Now the population of the village is 37 people, but most of them have lost their teeth, so they cannot whistle. In 2021, only 6 people spoke Sfiri fluently. Local residents are trying their best to preserve their language - they organize classes, write to the local administration with a request to open a school and invite scientists to record the sound of the language. Scientists learned about the Sfirian language only in 1969, when a plane crashed in the mountains near Antia. Members of the search party heard the shepherds talking in a whistling language. The range of communication in Sfiri can reach 4 kilometers.

In Mexico, Sochiapan Chinantec and Mazatec are used for whistling. The theoretical range of whistling can reach two kilometers, but residents prefer to communicate over short distances and for them it is more a way of socialization rather than a forced tool.

Residents of Mexican communities use whistling to speak in the market, a situation unique to whistling languages. Another surprising fact is that in Mexico only men communicate by whistling, although women usually understand what is being said.

In northern Turkey, in the village of Kuskoy, they speak the “language of birds.” It has been used in this area for many centuries and has approximately 10,000 speakers. In 2021, along with silbo gomero, it was included in the UNESCO list of oral and intangible cultural heritage in need of protection. Every year the village holds a festival dedicated to the traditions, history and culture of bird language. Recently, it began to be studied in primary schools and the Turkish University of Giresun at the Faculty of Tourism.

The Hmong people, who live in the foothills of the Himalayas in Vietnam, have their own version of a whistling language that is used by hunters and farmers. However, it has another popular use - courtship language. Although rarely practiced today, young people used the Hmong whistling language as a flirting language. The boys wandered around the villages whistling poems to attract the attention of girls. If the girls reciprocated, this could be the beginning of a relationship.

***

Rapid developments in technology have significantly reduced the need for whistling, but network coverage still suffers in high mountain areas. Elderly residents of whistling communities try to pass on their knowledge to young people, participate in festivals dedicated to language traditions and often ignore mobile phones, preferring to communicate using a proven method. Teenagers resort to whistling much less frequently, but still periodically practice and become interested in the ancient skill. For them, this is a way to get closer to history and understand the origins of local traditions. From time to time, another important feature of whistling comes in handy - it can quickly convey information that is not intended for other people's ears. One way or another, whistling tongues remain a unique phenomenon, many of whose mysteries have yet to be revealed.

Setting the sound

Pronouncing the sound T in the lower articulation, the tip of the tongue at the lower gum, while simultaneously moving the tongue back: T-S.

2. Quickly pronounce a combination of sounds (ATS)

Ts are usually automated from reverse syllables (ATs, Yts...)

Speech therapists!

Add your methods of making whistling sounds in the comments or write what methods of making whistling sounds you usually use.

If you found this information useful, share it with your friends on social networks. If you have questions on the topic, write in the comments. Your online speech therapist, Natalya Vladimirovna Perfilova.

Mechanical assistance

If the tongue is not held behind the teeth, but jumps out, then mechanical support is needed. You can hold the child’s tongue in the slide pose using:

- finger (pre-washed)

- massage or special staging probe

- toothpicks (break off the sharp edge)

- matches (not sulfur head)

- cotton swab

while practicing gymnastics at the same time:

- tube with tongue

- pancake

- brushing the lower teeth

- comb your tongue

- roll the reel

- fence - tube with lips

breathing exercises:

- blow the cotton wool off your tongue between your lips

- between teeth

- downhill

- match from the hill

voice

- pull out the sounds I, A, E in the slide position

tongue and lip massage

Then all these skills worked out separately are combined, holding the child’s tongue and blowing away the cotton wool. He holds the slide, pulls out “iiiiii”, then adds “ssssss” - sometimes whistling ones are better placed in reverse syllables - AS, IS, ES, YS, you can use US and OS, but at the same time you need to clearly make a “pipe-fence” with your lips. If first “ssss” and then “iii”, then it will be Sb, which is also not scary, then it’s not difficult to make a hard sound from it, pressing the back of the tongue with a probe.

![Letter L and sound [l]](https://pleshakof.ru/wp-content/uploads/bukva-l-i-zvuk-l-330x140.jpg)